Convergence

October 10, 2016

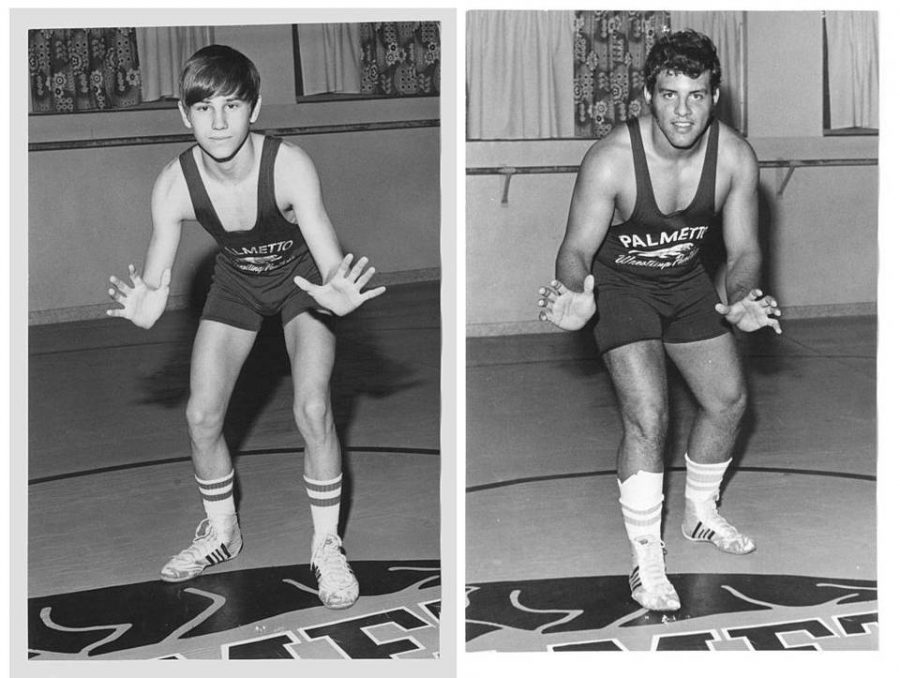

Two alumni Palmetto wrestlers cross the borders of friendship throughout their lives, and it started with the craving for competition

The Lightweight

Kevin Pedersen lives each day with his past and Christ in mind. He served in the military and became the highest award-winning Drug Enforcement Agency agent in history. He graduated from West Point in New York. He conducted undercover master investigations on local and international scales. But before that he wrestled at Miami Palmetto Senior High.

Pederson, commonly known as “coach” among his players and acquaintances, wrestled for Coach Barry Zimbler at Palmetto from 1974-76 with his close friend Alex DeCubas. The two met when they were kids playing little league baseball, opponents across the clay. At Palmetto Junior High, now named Palmetto Middle, they sealed their friendship with dueling natures, but shared an obsession with competition. They joined the wrestling team.

“Wrestling was the center of our friendship,” Pedersen said.

For Pederson, wrestling was always there. His family – natives of Iowa, where wrestling remains a highly-valued sport – not only a means of competing, but an essential part of learning self-defense. He and DeCubas served as captains of both their junior high and high school wrestling teams, and remained undefeated except for the day they came short of securing the 1975 State Championship. They won the State Championships in 1974 and 1976, their sophomore and senior years.

“Wrestling is the toughest sport in high school, and the guys that come out of that are going to be successful,” Pedersen said. “They don’t even know what the word ‘quit’ is.”

For both DeCubas and Pedersen, the craving for competition and unrelenting persistence posed problems and solutions to the events they faced in their lives.

“You learn from wrestling to get back up and keep pressing on and take what you learn and get better,” Mike Pedersen, Kevin’s older brother and former Palmetto wrestler, said. “Kevin decided the heck with this, I’m going to get better and go on with life.”

After high school, Kevin Pedersen graduated from West Point and served in the military.

“My first year at West Point I wanted to quit and come home,” Pedersen said. “My dad said I could quit but I couldn’t come home, so I figured I’d better stay.”

Pedersen was the student with straight As and a strong conscience who in high school made it to the Teachers’ Hall of Fame – a since lost Palmetto tradition where teachers select the highest-achieving students for the honor. He hopes to inspire the same kind of integrity and hard work in his players as a coach.

“My goal is to make every young person I come in contact with to be a better person, and to achieve all that they can achieve,” he said.

In the midst of his accomplishments, drug abuse affected Pedersen’s life when his ex-wife became an addict. He filed for a divorce. She took his son, he lost his house, and life became unbearable. He considered committing suicide; he decided to pull the trigger.

“I was going to shoot my head off,” Pedersen said.

He abstained.

“I gave my life to Christ at that moment, and I realized that the gun ended up on the other side of the room by some force other than my own,” Pederson said.

It was at that moment he decided to shift the direction of his career and of his life.

“The next few days I spent in my room praying,” Pedersen said. “God made it real clear to me that I would go into law enforcement.”

He joined the DEA, and within a year was involved in investigations on local and international levels, specifically pertaining to the drug industry. As Kevin collected awards for his service, Alex collected cash dealing cocaine from Colombia.

“It was a tough life but it was an exhilarating life because I could put the worst away,” Pedersen said. “At that time, Alex was on the run and still running the drug business and was a wanted man in the U.S., so he was looking over his shoulders all the time. Now I’m coaching a little high school wrestling team, which is different from handcuffing a guy.”

Pedersen stayed in touch with DeCubas throughout his jail sentence, occasionally grabbing a bite for lunch while he was on probation. Pedersen decided to bring the friend he knew in high school back to wrestling.

“I was concerned about his mental state, his emotions and his view on the world,” Pedersen said. “The best way to [fix] that is to help others, and one way to give to others is to coach.”

He spoke with his administration at Westminster Christian High, where he began coaching the wrestling team four years ago, to suggest an assistant coach position for Alex. With the consent of the parents, Alex became Kevin’s coaching partner in 2015.

“That was the perfect place for Alex to come,” he said. “There’s a lot of … people there who understand forgiveness.”

Soon thereafter, however, Kevin received negative feedback from his friends and fellow wrestlers from his high school days. He was “insane.” They said, it was “wrong” for Kevin to pitch the job opportunity to the school for DeCubas. But in his heart, Pedersen believes he made the right decision.

“It’s a story of redemption, second chances and relationships that obviously go all the way back to middle school and high school, and what can you do with them 40 years later,” he said. “We trust each other. We’re honest with each other. We have wrestling in our competitive nature, and [we have] great desire to win at anything.”

Wrestlers for Life

Retired NASA astronaut and U.S. Navy Officer Dominic “Dom” Gorie wrestled alongside Pedersen and DeCubas, in addition to playing football for the Panthers, before graduating high school in 1975. Gorie attended Palmetto in part due to the athletic program’s notable reputation at the time just a couple years after he and his family moved to Miami from Illinois.

“The structure and demand and what it takes to succeed in wrestling was transferrable to almost anything I ever did,” Gorie said. “At the naval academy that required an amount of focus, structure and motivation, [and] at NASA it was the same thing.”

Though most of the wrestlers were invested in the sport, some also had ambitions of their own, like Gorie’s persistent dream of becoming a NASA astronaut.

“When I was 8 or 10 years old and watching the first steps to get man into space I remember thinking that’s incredible, that’s like playing in the Super Bowl or pitching in the World Series,” Gorie said. “I knew I could become a pilot and fly but always in the back of my mind there was this goal, this dream, of getting to do that.”

When Gorie looks back on his memories in high school, however, they always come back to the GMAC wrestling tournaments and championship matches.

“Any time you go through something as grueling and demanding and rigorous as a wrestling program, you develop a kinship of brotherhood that’s almost unrivaled in any other sport,” Gorie said. “Because wrestling is smaller than other sports teams, you develop friendships that I think last a lifetime, and that’s because of that common bond of going through something really tough together.”

In terms of the life lessons they learned as a team, Gorie traces them back to Coach Zimbler.

“Whenever you have a wrestling coach that you spend a lot of time with, you develop a relationship that is close to a parental relationship,” Gorie said. “Coach Zimbler was held in high esteem and everyone, including myself, respected what he said and tried to do their best to meet those expectations. We were better young men because of him.”

Gorie can speak from experience. A large frame takes up the space on the wall perpendicular to the encased athletics trophies displayed in the main entrance of the school. Hundreds of Palmetto students walk past it each day, but few stop to look at it. Inside, pictures of Gorie as an astronaut and certificates honoring his achievements boast Panther Pride through the glass.

“What I learned was that if you learn those two rules of achieving and striving to be the best that you can be, then your future is unlimited,” Gorie said. “For me, what I was able to do was unexpected, and I would say totally that the biggest factor of that was Palmetto wrestling.”

The Heavyweight

When young Alex DeCubas first laid eyes on Pedersen playing Little League baseball at Suniland Park, he could not have imagined the relationship that they would build, break and finally remend once again nearly forty years later.

DeCubas was born in Cuba but moved to Miami with his family at just 18 months old. As a 170 pound sixth grade boy who had an itch for contact sports, DeCubas could not play football for Suniland with its 145-lbs-or-less requirement. To compensate, he played baseball at Suniland – which had no weight restrictions – and joined the Palmetto Junior High wrestling team in the 180-lb class.

He and Kevin formed a friendship there, bonded on the common grounds of wrestling under Coach Walt Allison.

DeCubas’s success in wrestling seemed inevitable in high school: he proved himself as one of the strongest wrestlers in junior high, and in 1974 during his sophomore year, the Palmetto wrestling team won the state championship.

“It was a thrill, and the sport had such a great backing. The gym was jam-packed in just about every match.”

The gym – hidden behind the halls of the 900 building, no longer used for Palmetto’s current indoor sporting events – hosted crowds of people each match, with stranded spectators peering in through the windows from outside on the roof.

DeCubas’ parents often supported him at his matches, and his father in particular made an effort to attend every one of them, including the matches at the University of Georgia, which recruited Alex for wrestling among more than seven other schools.

“My father was a great fan of mine and of the sport, and my parents were both very important to me,” Decubas said. “They always made time to come and visit me.”

In addition to support from his family, DeCubas owed much of his strength and character as a wrestler to his coaches.

“I was so captivated by the sport, and the whole technical and strength factor I really enjoyed,” DeCubas said. “I was blessed with excellent coaches throughout my career.”

Alex received a call – and a summoning home – from his uncle in Miami during his sophomore year at UGA. When he returned home, he found out that his father shot himself in a back office of the clothing boutique he owned. The man who always referred to Alex as his “tiger”, his pride and joy, had vanished from DeCubas’ life.

Soon afterwards DeCubas dropped out of UGA and moved back to Miami, where he eventually found himself dealing drugs in the midst of Miami’s large drug-dealing scene in the late ‘70s.

“I didn’t just wake up one morning and decide I wanted to deal drugs,” DeCubas said. “It was a progression of getting myself deeper into illegal activities and dealing with drug cartels. Once you get indicted in the U.S. judicial system, it never ends.”

He sought a way to overcome the law that restrained him.

“When I was indicted and I was living here, I had everything in my life but it was either stay here and face a life sentence, or pack up and leave and hope for the best, so it was an evolution that got me deeper and deeper into the trade that I was involved in,” DeCubas said.

The trade he was involved in tainted his image. In the aftermath of his father’s unexpected death and dropping out of college and the wrestling career he loved, he turned to quick cash and late-night parties, essentially becoming someone his old friends, including Kevin, no longer recognized.

Yet the kind-hearted, passionate boy his friends and family knew in high school had not completely disappeared, and DeCubas recognizes his own altered sense of morality.

“I know the clear line between right and wrong. I’m not going to walk into the store and walk out without paying for it,” DeCubas said. “During my days of criminal activity I tried to bend everything around – fake IDs, fake name, everything was corruptible with money back then, so my sense of normalcy is very different from normal working people.”

Beneath the thick layer of drugs, cash and fame, DeCubas earned as one of the biggest names in the Colombian cocaine industry during the ‘80s and ‘90s was a loss that DeCubas feels can never be replenished.

“I would have loved to be able to change things because I lost the most precious years of my son’s life and I can never get that back, if I only knew what I know now,” DeCubas said. “I lost 23 years of being able to be a father to my son. I spent 13 years as fugitive in Colombia, and 10 years in prison. No money can ever repay that. Those years are gone.”

At DeCubas’s sentencing after he was incriminated for his drug activity and arrested in 2003, Kevin stood behind his old wrestling buddy, unbeknownst to Alex. He went for support; he went to help Alex get back on track.

“I didn’t even know he was in the audience, and later on he arranged to meet me with the attorney and prosecutor and offered his support,” DeCubas said. “When I got out, our old wrestling team invited me to honor Coach Zimbler, and Kevin was there and that was the first free contact with him I had.”

That was in 2012, when DeCubas was released early, and just a month later his old teammates invited him with open arms to attend a celebration commemorating Coach Zimbler’s John & Helen Vaughn Award and induction into the National Wrestling Hall of Fame, the first in Florida.

From that point on, things began to look up for DeCubas, and in time Pedersen approached him with his offer to make him his assistant wrestling coach at Westminster Christian High.

“I’m just a normal guy who got involved in some crazy stuff,” he said.

And the community is behind him.

“He’s finding that even after all of that stuff, he’s finding out that he can still be a positive impact on young people,” Gorie said. “And I think that’s going to change his life.”