Want to ban books?

March 18, 2017

A girl named Scout recounts when her older brother Jem broke his elbow, so begins one of the most famed and daring literary creations of all time, “To Kill a Mockingbird.” To the poor souls who have yet to read Harper Lee’s novel that has made banned book lists across the country for decades, this opening line makes little sense without context. But within the pages bound by its spine – and, many times, between the lines of Lee’s sentences – lies a much more profound statement about the South, about the loss of innocence and about people.This past December, the mother of a biracial high school student in Virginia complained of the frequent use of the n-word in novels like “Mockingbird” and Mark Twain’s “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” two novels most of us have read as required reading in the Miami-Dade County Public School system. She toted her complaints with her to a school board meeting, and wouldn’t you know, their school district agreed to ban Lee’s and Twain’s iconic novels from all shelves in their school libraries.

This past December, the mother of a biracial high school student in Virginia complained of the frequent use of the n-word in novels like “Mockingbird” and Mark Twain’s “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” two novels most of us have read as required reading in the Miami-Dade County Public School system. She toted her complaints with her to a school board meeting, and wouldn’t you know, their school district agreed to ban Lee’s and Twain’s iconic novels from all shelves in their school libraries.

Allow me to begin softly on this issue – or, actually, how about I don’t.

The Virginia school board’s ban on classic literature that has continued to pave the way for social justice openly reveals its ignorance. The Los Angeles Times quoted the mother saying that though she agreed the novels represent great literary achievement, the amount of racial slurs contribute to making us a “nation divided”. Okay, racial slurs certainly pop up in the prose of both novels – approximately 200 times in “Huckleberry Finn” and 50 times in “Mockingbird,” according to the LA Times – but neither author used them to degrade racial minorities. Although this concerned mother has probably had her share of schooling, any properly educated person knows that these two novels contain some of the most anti-racist ideas in classic literature. Of course, both novels feature characters who spew blatantly racist thoughts, but the authors used these characters to condemn racism.And, for the record, our nation has always been divided. Since the antebellum era, race relations have taken an enormous turn for the better, but we have yet to eliminate divisions entirely. It is a completely invalid argument that holds no support whatsoever.

The mother continued to say — get ready to cringe — that by allowing students to read these novels, adults “validate” that they are acceptable. Her argument is the poster child for every manual on the shelves about fallacies. Words printed on a page do not “validate” their use in modern society. Say a student reads “Mockingbird” in class. He or she will see the use of these slurs frequently in the characters’ dialogue for two painfully obvious reasons: one, that the novel is set in the 1930s, when people freely used these terms as part of the social norm, and two, that without these terms, neither novel would possess neither the realism nor poignancy that elevates them to sophistication. Lee intended for the n-word to paint an accurate portrait of society in her childhood hometown and to draw attention to the inhumanity of the word; Twain used the n-word in a straightforward satire against racism in a literally divided United States.The aforementioned novels, however, were not the only two placed on a banned book list since their

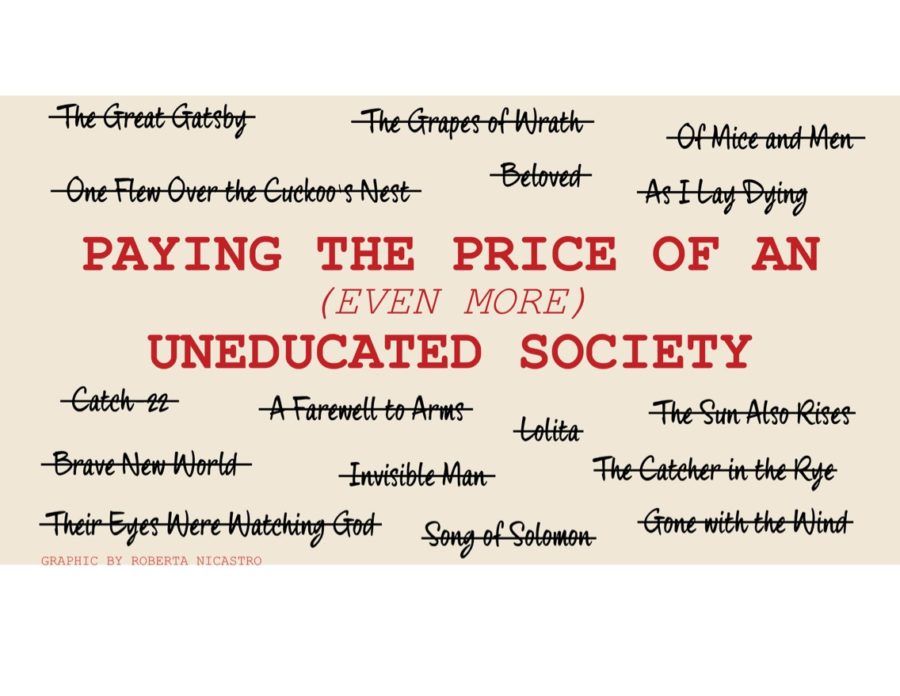

The aforementioned novels, however, were not the only two placed on a banned book list since their printiversary. The length of the list is astounding – and the titles are even more shocking. They, and the authors who breathed life into them, continue to leave a deep impression on all who read through their pages. Even the oldest novels, their pages withering with antiquity beneath a layer of dust, take on new meanings for new generations.The authors who dared to write against the status quo are those whose words have influenced history. The stories of the Lost Generation expatriates blended outspoken reality with a yearning for a freedom, as in Hemingway’s “A Farewell to Arms” and Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby.” Zora Neale Hurston took all existing literature by the horns and wrote a story that encapsulated the lives of African-American women in the early 20th century in “Their Eyes

The authors who dared to write against the status quo are those whose words have influenced history. The stories of the Lost Generation expatriates blended outspoken reality with a yearning for a freedom, as in Hemingway’s “A Farewell to Arms” and Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby.” Zora Neale Hurston took all existing literature by the horns and wrote a story that encapsulated the lives of African-American women in the early 20th century in “Their Eyes Were Watching God.”These titles were banned out of fear: fear of the unknown, fear of diversity, fear of change. Only in the face of fear does authority step forward and make the cowardly decision to strike something down, when it is too strong to go down without a fight. Anyone recall when jedi master Obi-Wan Kenobi became more powerful after Vader struck him down with a swing of his lightsaber? The authorities in our society have encountered the same problem — because the books that were once banned are arguably the most well-known, highly acclaimed and ever-lasting pieces of literature of all time.

These titles were banned out of fear: fear of the unknown, fear of diversity, fear of change. Only in the face of fear does authority step forward and make the cowardly decision to strike something down, when it is too strong to go down without a fight. Anyone recall when jedi master Obi-Wan Kenobi became more powerful after Vader struck him down with a swing of his lightsaber? The authorities in our society have encountered the same problem — because the books that were once banned are arguably the most well-known, highly acclaimed and ever-lasting pieces of literature of all time.

Impressive words and politically correct grammar do not make a piece of literature great; it’s the impact on society that raises a novel from average to awe-inspiring.

And so it is our job, as the youngest generation of readers, to take on a dangerous challenge: for the authors who dared to speak out against society’s ails, we must dare to appreciate them with even more vigor and use them to speak out against our world today.

Banning great literature in our “divided nation” is counterproductive; only by learning from great literature can we begin to mend the fissure between us.